Upon beginning Jane Eyre I knew this about Charlotte Bronte -

She was an author.

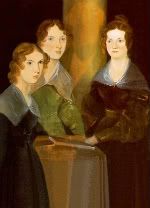

She had two sisters, Emily and Anne who were also authors.

Not much, huh?

My edition of Jane Eyre has an excellent forward written by Susan Ostrov Weisser. Honestly, sometimes I skip forwards because I find them to give away too much of the story - I find them to be written assuming the reader has already read, or already knows the story. In this case, since I already knew an outline of the story, I decided to go for it and read the forward.

Charlotte Bronte was born on April 21, 1816, in Thornton, Yorkshire - Northern England. Charlotte was the third child of six - Maria, Elizabeth, Charlotte, Patrick (known as Branwell), Emily, and Anne. Her father was a reverend, and when her mother died in 1821, her aunt, Elizabeth Branwell, moved in to help raise the children. Upon her arrival, the four eldest girls were sent to Cowan Bridge School.

Cowan Bridge School was intended to educate poor clergymen's daughters, and under the direction of Reverend William Carus-Wilson; the man upon whom Charlotte modeled Reverend Brocklehurst. The children at Cowan Bridge School were highly regimented and lived in unhealthy conditions. Rev. Carus-Wilson believed in teaching the pupils self-denial and unquestioning submission, and strict religious and moral principles. As a result, the children in attendance suffered from insufficient and poor-quality food, lack of heat, and disease. Not surprisingly, Charlotte's experiences at the Cowan Bridge School inspired the Lowood School in Jane Eyre.

Charlotte's two older sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, died in 1825 from tuberculosis. Charlotte and Emily were removed from the Cowan Bridge School.

The remaining Bronte children studied at home and began writing. They were very cut-off from the outside world, and would write plays, stories and poems for amusement. Their father brought home toy soldiers for play, and the children each chose a favorite (Charlotte's was called Wellington). From here, the children wrote extensive stories and fantasies involving their soldier. The children were incredibly self-sufficient and lived lives rich in imagination, especially considering the fact that they were being raised by a father who was very detached, and a strict and religious aunt.

When Charlotte was fifteen, she was sent to the Roe Head school. She felt very awkward and self-conscious, especially after living much of her childhood separated from children not part of her immediate family.

Charlotte taught at Roe Head from 1835-1838, and was a governess in 1839 and 1841. She was miserable in this vocation without enough time to write.

Meanwhile, Charlotte's brother, Branwell, was educated to be a portrait painter. After failing at this career, he became dependant on alcohol and opium, dying young. Ironically, his most famous works are the portraits of his sisters.

Charlotte longed to write, and sent her poems to British poet, Robert Southey. He answered her:

In 1842 Charlotte and Emily went to school at the Pensionnat Heger in Brussels. Their intention was to acquire the skills to open their own school. Unfortunately, their dream of a school did not become a reality.

In 1846, Charlotte, Emily and Anne published a book of combined poetry under the pseudonyms Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell, respectively. Although only two copies of the book were sold, this endeavour got their foot in the door, so to speak. In the two years that followed, Emily published Wuthering Heights, Anne published Agnes Grey, and Charlotte published Jane Eyre. All three novels were published within months of each other, and there was much controversy over the gender of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell.

Jane Eyre received mixed reviews. One reviewer was offended by the unchristian nature of Jane's undisciplined spirit. This reviewer called the book unfeminine.

Soon after these publications, both Emily and Anne quickly succumbed to tuberculosis. By 1849, all that was left of the Bronte family was Charlotte and her father.

In 1854, Charlotte married Arthur Bell Nicholls. He had been a suitor for many years, however Charlotte was not in love with him. His devotion won her over and although she did not feel herself in love, she was happy in her new life. Within months she became very ill and died in March, 1855. At the time, her death was linked to pregnancy, although this was never proven.

What an interesting woman.

At this point, I'm about halfway through Jane Eyre. I was expecting it to read like Jane Austen and was pleasantly surprised (although I love Austen) to find it, in many ways, plainly written. A highly accessible novel. Even though I do not agree with the reviewers at the time, I can see where the novel was criticized as being "coarse". If readers of the time were expecting prose akin to Austen, they were in for a surprise.

Knowing Charlotte's story has given her novel new meaning. All my information was obtained from Susan Ostrov Weisser's forward in my copy of Jane Eyre.

She was an author.

She had two sisters, Emily and Anne who were also authors.

Not much, huh?

My edition of Jane Eyre has an excellent forward written by Susan Ostrov Weisser. Honestly, sometimes I skip forwards because I find them to give away too much of the story - I find them to be written assuming the reader has already read, or already knows the story. In this case, since I already knew an outline of the story, I decided to go for it and read the forward.

Charlotte Bronte was born on April 21, 1816, in Thornton, Yorkshire - Northern England. Charlotte was the third child of six - Maria, Elizabeth, Charlotte, Patrick (known as Branwell), Emily, and Anne. Her father was a reverend, and when her mother died in 1821, her aunt, Elizabeth Branwell, moved in to help raise the children. Upon her arrival, the four eldest girls were sent to Cowan Bridge School.

Cowan Bridge School was intended to educate poor clergymen's daughters, and under the direction of Reverend William Carus-Wilson; the man upon whom Charlotte modeled Reverend Brocklehurst. The children at Cowan Bridge School were highly regimented and lived in unhealthy conditions. Rev. Carus-Wilson believed in teaching the pupils self-denial and unquestioning submission, and strict religious and moral principles. As a result, the children in attendance suffered from insufficient and poor-quality food, lack of heat, and disease. Not surprisingly, Charlotte's experiences at the Cowan Bridge School inspired the Lowood School in Jane Eyre.

Cowan Bridge School

Charlotte's two older sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, died in 1825 from tuberculosis. Charlotte and Emily were removed from the Cowan Bridge School.

The remaining Bronte children studied at home and began writing. They were very cut-off from the outside world, and would write plays, stories and poems for amusement. Their father brought home toy soldiers for play, and the children each chose a favorite (Charlotte's was called Wellington). From here, the children wrote extensive stories and fantasies involving their soldier. The children were incredibly self-sufficient and lived lives rich in imagination, especially considering the fact that they were being raised by a father who was very detached, and a strict and religious aunt.

When Charlotte was fifteen, she was sent to the Roe Head school. She felt very awkward and self-conscious, especially after living much of her childhood separated from children not part of her immediate family.

Charlotte taught at Roe Head from 1835-1838, and was a governess in 1839 and 1841. She was miserable in this vocation without enough time to write.

Meanwhile, Charlotte's brother, Branwell, was educated to be a portrait painter. After failing at this career, he became dependant on alcohol and opium, dying young. Ironically, his most famous works are the portraits of his sisters.

Charlotte longed to write, and sent her poems to British poet, Robert Southey. He answered her:

"Literature cannot be the business of a woman's life, and it ought not to be. The more she is engaged in her proper duties, the less leisure she will have for it, even as an accomplishment and recreation. To those duties you have not yet been called, and when you are you will be less eager for celebrity."Charlotte's response?

"In the evenings, I confess, I do think, but I never trouble anyone else with my thoughts... I have endeavoured not only attentively to observe all the duties a woman ought to fulfill, but to feel deeply interested in them. I don't always succeed, for sometimes when I'm teaching or sewing I would rather be reading or writing; but I try to deny myself. ...Once more allow me to thank you with sincere gratitude. I trust I shall nevermore feel ambitious to see my name in print; if the wish should rise, I'll look at Southey's letter, and suppress it."Charlotte was clearly destined to create a piece of classic literature which asserts the rights of women.

In 1842 Charlotte and Emily went to school at the Pensionnat Heger in Brussels. Their intention was to acquire the skills to open their own school. Unfortunately, their dream of a school did not become a reality.

In 1846, Charlotte, Emily and Anne published a book of combined poetry under the pseudonyms Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell, respectively. Although only two copies of the book were sold, this endeavour got their foot in the door, so to speak. In the two years that followed, Emily published Wuthering Heights, Anne published Agnes Grey, and Charlotte published Jane Eyre. All three novels were published within months of each other, and there was much controversy over the gender of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell.

Jane Eyre received mixed reviews. One reviewer was offended by the unchristian nature of Jane's undisciplined spirit. This reviewer called the book unfeminine.

Soon after these publications, both Emily and Anne quickly succumbed to tuberculosis. By 1849, all that was left of the Bronte family was Charlotte and her father.

In 1854, Charlotte married Arthur Bell Nicholls. He had been a suitor for many years, however Charlotte was not in love with him. His devotion won her over and although she did not feel herself in love, she was happy in her new life. Within months she became very ill and died in March, 1855. At the time, her death was linked to pregnancy, although this was never proven.

What an interesting woman.

At this point, I'm about halfway through Jane Eyre. I was expecting it to read like Jane Austen and was pleasantly surprised (although I love Austen) to find it, in many ways, plainly written. A highly accessible novel. Even though I do not agree with the reviewers at the time, I can see where the novel was criticized as being "coarse". If readers of the time were expecting prose akin to Austen, they were in for a surprise.

Knowing Charlotte's story has given her novel new meaning. All my information was obtained from Susan Ostrov Weisser's forward in my copy of Jane Eyre.

Comments

Post a Comment